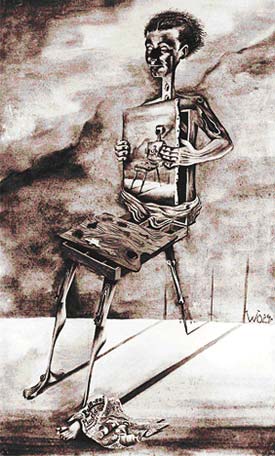

Wolf self-portrait

Paris 1936

Master Painter Adolf vs. Master Painter Wolf

Wolf Cartoon, Paris 1936

Text © 2006 by Alpine Guild, Inc.

Illustrations © 2006 by Peter Natan

All Rights Reserved

1940.

Outside Paris. January. A hundred or so men are crowded into an old building that may have once been a warehouse. Some sit on the few benches along the wall. Others stand. Some sit on the floor. The air is heavy with cigarette smoke. The light from a few bare bulbs barely breaks the gloom.

Outside the building, the skies are leaden and a cold drizzle is falling. Through the dirt-streaked windows of the building can be seen other drab buildings where now exist over a thousand men. Around the buildings there is a tall barbed wire fence and beyond the fence are dark, sodden farm fields.

At one end of the building there is a scarred wooden table. Behind the table sits an official, wearing a wrinkled uniform. He has a large stack of papers in front of him. He is a gray, lumpy man, balding, wearing pince nez glasses which he often removes to rub his eyes and nose. Across the table from him there is a chair, occupied now by an even older man, wearing a heavy overcoat. The official closes a folder, raises his hands in a gesture of futility, and waves the older man away. Then he shuffles through the papers, chooses a folder, and looks up.

"Hamburger, Wolf Hamburger," he calls out. A thin young man with an aquiline nose and a shock of black curly hair gets up from the floor, stubs out his cigarette, and walks slowly to the table.

"Be seated," the official says, waving toward the chair. The young man sits down.

"So," the official says, not looking up from the papers, "you are a German citizen and France is now at war with your country."

The young man stiffens. "No," he insists "I am not a German citizen. I left that country and I came to France."

"You had a German passport when you came. You were a German citizen. However, I see that your passport has expired. Why didn't you renew your passport? Why didn't you go back to Germany before the war started? You also went to Palestine recently. Why didn't you stay there?"

The young man answers. "I am an artist. Paris is the place for serious artists and that is why I came to France. Anyway, you can see from the papers that I am also a Jew. In Hitler's Germany, they are killing Jews. I could not go back there."

"Ah, yes," the official says. "A Jew. A former German. Now a stateless person."

The official softens his tone. "Wolf, I have seen some of your cartoons in the press. You draw very well. You must be a fine artist, even if your cartoons surely make the authorities uncomfortable. But there is no longer time for clever cartoons, no matter how well drawn."

"How long will I be here?" Wolf asks.

"Who can say?" The official shrugs. "You were arrested by the police because you are or were a German and because you had no valid passport. All suspect foreign persons will be interned for the duration of the war. Who knows how long that might be."

There is a silence. The official seems to be waiting for Wolf to speak. Thoughts of years in this dreary camp rush through Wolf's head and he does not speak.

"Young man," the official finally says, "There is an alternative. I have been allowed by the authorities to offer certain internees an opportunity to leave the camp under certain circumstances. I believe you would be qualified. You are young, healthy, stateless. You are just the sort of man that the Foreign Legion wishes to enlist."

Wolf sits up and his hands clench and unclench. "The Foreign Legion?" he almost shouts. "You have seen my cartoons. You must know how I feel about war, about killing. How could I join the Foreign Legion and kill other men?"

The official shrugs. "Of course, before the war began you could indulge your anti-war feelings. Even I could understand those feelings. But all that is now changed. We are at war with the Germans. It is said they are murdering your people, those who are left. Surely the Germans will attack France. The time for your squeamish attitude toward killing the enemy is now past."

"Even if I could learn to shoot at Nazis," Wolf replies, "I could not leave my wife Anne. She is very sick."

The official smiles a tolerant smile. "My dear young man, perhaps you have not understood the situation. You are interned in this camp. You will not be allowed to leave until the war is over. Your only way out of this camp before the war is over is to enlist in the Foreign Legion. Either way, I regret to say, you will not see your wife. Normal life for you is at an end. You must accept that and you must make the best decision for yourself and for your wife that you can."

He reaches for a group of papers on the far side of the desk. "Monsieur Wolf, I have here the enlistment papers for the Foreign Legion. A sergeant of the Legion comes here each week to enlist those who choose this opportunity. The enlistment is for five years. You will be sent to North Africa for training. However, before you go, the Legion gives its new enlistees two weeks in which to put their affairs in order. If you enlist, you will be released from this camp to go to your wife or wherever for two weeks before you are sent to North Africa. If you do not enlist, you will stay here for who knows how long."

The official shrugs. "I see that you do not care for the choice. But there are no others. Think about the opportunity I have offered. The sergeant will return here in a few days. I want your decision before he returns. There is nothing more to say."

With those words, the official closes Wolf's folder with an audible snap, shoves it into a pile and reaches for a new folder. "Adieu, Monsieur Wolf.

Wolf Hamburger gets up and makes his way back into the crowd of men. Another name is called and another man proceeds to the table. Wolf's mind races with the thoughts that crowd in. If only he could talk with Anne. But he must make this decision alone.

He and the other internees have discussed their situation many times. There is little news from the outside, but they know that Germany invaded Poland in September and in only a few weeks conquered that country. France and Britain declared war on Germany. Then the police began to pick up the men who were now in the camp.

There has been no warfare since Poland fell. The Germans seem to be gathering their strength for a blow against France and the countries of the lowlands to the north. French politicians claim that the French and British armies will crush the Germans. French generals claim that the Maginot line, a line of fortifications along the French-German border will stop the German army. But no one believes any of these claims. Before they were brought to the camp they could see for themselves how poorly the French were prepared for war.

In the camp the internees often discuss what might happen. All believe that the German army will quickly overrun France. Wolf and the other Jews in the camp are sure that if this happens they will be at the mercy of the Gestapo and the SS, the cruel instruments of Hitler's campaign to exterminate Jews. Wolf knows that his anti-Nazi cartoons will specially mark him for the Gestapo.

As Wolf thinks about his alternatives, each seems more hopeless than the other. If he chooses to enlist in the Foreign Legion he will be sent to North Africa and then into battle. The Foreign Legion is always at the forefront of the fiercest fighting and he will not only have to kill but he is likely to be killed. He will be separated from Anne, possibly forever.

If he decides not to enlist, he will be in this internment camp when the Nazis take over and he and the other Jews will be sent to camps in Germany, probably never to return. He will be separated from Anne, almost certainly forever.

For several days he talks with other internees. For several nights he barely sleeps as he considers the choice he must make. Finally, he makes his decision. He asks to see the camp official.

"Ah, Monsieur Wolf," the official says, removing his glasses and rubbing his nose, "Am I to understand that you have reached a decision on your future?"

Wolf looks the official directly in the eye. "I have decided to enlist in the Foreign Legion."

Later that week, Wolf meets with the Foreign Legion sergeant, a short, swarthy man of indeterminate nationality. Wolf signs documents, swears an oath, and receives a perfunctory physical, given by the sergeant.

The following day, Wolf is given papers that allow him to leave the camp and direct him to report, in two weeks, to the Foreign Legion headquarters in Paris. He walks out of the camp, and trudges under gray skies to the railroad station. Soon he is back in Paris. Then he boards another train to go to the suburb of Chatenay Malabry. He hurries from the station to the small apartment in which he and Anne have lived.

She is there when he bursts through the door. They embrace and then the words tumble out. There is so much to say and so many kisses to be exchanged.

Anne has not recovered well from the spleen operation she had months before in Palestine. While Wolf has been gone, she has become even more ill. She looks pale and thin. She tells him little of her troubles. She wants to hear about him.

He tells her of the choice that he made. He has two weeks -- only two short two weeks with her. Surrounded by Wolf’s easels, paints, brushes, pens, as well as paintings and drawings in various stages of completion, they discuss what the future holds and how they might use the precious hours that remain.

She tells him of the war. There are rumors of the German invasion, but nothing has yet happened. Paris, famous as "The City of Light", is dark, its lights doused in a blackout. There are shortages as the government requisitions more and more for the war effort.

"Our friends who have opposed the Nazis and the Fascists expect the worst," she says. "Hitler and Stalin made their non-aggression pact. Then they divided up Poland. Our Communist friends had counted on the Russians to bring down Hitler. They cannot believe what has happened. Some have killed themselves rather than accept that the Communists and the Nazis have joined forces. There is no place to turn for people like us."

Wolf nods his head. "In the camp, we all agreed that the Germans could not be stopped without Russian help. The French and British will never be able to do it by themselves. It is only a matter of time before the Nazis are marching into Paris and down the street in front of our apartment."

They discuss what they can do. It is clear to both of them that Anne is too ill to make a difficult run for a neutral country. Wolf would be a deserter from the Foreign Legion, with no passport or travel papers, and the police would be looking for him. With Anne ill, they would easily be caught within days if not hours.

Anne urges Wolf to leave her and make his own escape. But he refuses to even consider this. His voice drops to a lower tone and takes on a ferocious intensity. "Anne, I will never leave you!"

As they talk, they finally come to an agreement about what they must do. The joyous private world they have created for themselves will soon come to an end.

1917.

Max Wolfgang Shalom Hamburger is born on January 23, 1917, in Berlin, the capital of Imperial Germany. The Great War of 1914-1918, World War I, is in its third year. On the Western Front, thousands of men are being slaughtered each week in brutal but fruitless battle. Wolf's father, a loyal German citizen, had tried to enlist in the German army, but had been turned down because of a heart condition. The streets of the city are filled with men in uniform, many swathed in bandages or missing an arm or a leg. Food and coal are rationed. The city is shabby and dirty. Most of its workers have been called to the Army or to work in munitions or other war-related factories. The mood in the city and the nation is grim.

But the mood in the third floor apartment at Sybelstrasse 67 is one of joy. This is the first child born to Hertha and Kurt Hamburger -- a son, healthy, with black hair. The couple are happy with their good fortune and the war seems far away. They have named him Max for a relative. Kurt has chosen Wolfgang after his favorite composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Shalom -- "peace" -- is both a hope and a recognition of the baby’s Jewish heritage.

Kurt Hamburger, the father, is short, stout, intellectual. He is a gifted pianist, poet, composer. He is also an accomplished linguist, able to speak nearly a dozen languages. He has recently learned Hebrew.

His family has been in Berlin since 1640 and he can trace his family back to 1276 in Germany. The original family name was Natan, but a German law in the 1870's required that Jewish names be changed to German names. The family chose Hamburger in honor of long-ago ancestors who had moved to Berlin from the northern port city of Hamburg.

Kurt is not active in the synagogue, but he has become a Zionist at heart, eager to see a homeland for the Jewish people, even though he expects to live out his life in Berlin.

He works as an accountant in the clothing business owned by his wife's family, but music and literature are far more important to him than columns of numbers. When he is at home, he can usually be found at his piano or engrossed in a book.

Hertha, his wife, is an attractive woman, taller than Kurt. She has strong motherly instincts that now can be lavished on the new baby boy. She also maintains strong friendships with other women. Three times a week she and her friends walk to the Kurfurstendam, Berlin's main avenue. They always end up at the conditorei Kaffee Kranzler on the Ku-dam, as everyone calls the avenue, for a midday time of coffee, pastries, lively conversation, and close friendship. Wheeling a baby carriage along the avenue and into the shop is no problem. Hertha is immensely proud of her new son and her friends share the great joy that she brings to the conditorei table.

Hertha is a warm, outgoing person, far more interested in people than in books. She is happy and proud to show off the new baby to her many friends.

Hertha's family originally came to Berlin from Lubeck, another north German port city, where they were successful cloth merchants for nearly 100 years. Their name had been Levi, then Levin. In the 1890's, they were selling clothes from a horse-drawn wagon in the streets of Berlin. By the time the war began in 1914 the company occupied a small building at Orianienstrasse 40/41, in Berlin, where clothing for men and children was manufactured. Deutsche Compagnie Heitinger, the sign outside proclaims. Inside, clothing for men and children is manufactured. Most of the production now is uniforms for the army.

Hertha’s older brothers, Alfred and Erich, run the company. The business is doing well and Hertha and Kurt are able to live comfortably.

Even the war does not interfere with the good life the couple lead. There is always food, despite rationing. They enjoy a pleasant apartment with a maid. Everyone dotes on the new baby.

Hertha always calls the baby Wolfgang. But others soon shorten it to Wolf, a more affectionate nickname. He will never call himself Wolfgang. In time he will even drop his last name. His signature will just be "Wolf" or "Wo".

One evening, soon after the baby has arrived, Hertha and Kurt are in their living room. Kurt is reading, as he usually is. Hertha has been knitting baby clothes. Kurt looks up from his book. "Hertha," he says, "This Dr. Freud from Vienna has many interesting things to say in this book. He makes it clear that what happens to children in early childhood is very important. We must take care to see that Wolfgang is raised in the right way so he doesn’t develop psychological problems as he grows older. There must be books about this."

"Oh, Kurt," says Hertha, looking up from her knitting. "You read too much. Of course, children have to be raised the right way. But experience is the best guide. I have many friends who have children of their own. We often talk about the best way to raise our children."

"Kurt," she says firmly, "the old ways of raising children are wrong. Children need more freedom and less rigid control. German children have been treated as if they had to be ruled in everything by adults. Sometimes, I think that is one of the reasons for this terrible war -- we Germans accept too much what our leaders say."

"Well, of course, that is probably true," says Kurt, "but after all we do have to make decisions for baby Wolfgang. He is too young to decide things."

Hertha laughs. "Oh, I don’t mean right now. He is just a baby who eats and sleeps. But when he gets older we must let him develop on his own. We must give him the freedom to make his own decisions. We want him to be independent."

Kurt picks up his book again. "I hope I can help him to love all the good things of music and literature and art. Dr. Freud isn’t much help in this." Then he goes back to reading. There are tentative cries from the next room and Hertha gets up to tend to the new baby.

While the Hamburgers learn how to feed and take care of the infant Wolf, their world is being irrevocably changed. 1917, the year of Wolf's birth, will be a turning point. The events of this year will shape the world until our own time and beyond.

The "Great War" or World War I, began in August 1914. It has been called the "Stupid War" because its causes do not seem important enough to bring about such enormous bloodshed and disaster. Many historians believe that the stubborn pride, short-sightedness, and plain foolishness of a handful of leaders actually caused the war. Kaiser Wilhelm in Germany, the leaders in Britain and France, and Tsar Nicholas II in Russia all believed it would be a short war. Each side expected to easily win the war in a few months. They were all dreadfully wrong.

The Germans, along with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as Bulgaria and Turkey are on one side of the fighting. This coalition is called the "Central Powers." Against them are France, Britain, Russia, Italy, and several smaller countries. This group is called the "Allies."

By the time of Wolf’s birth in 1917, the war has been going on for nearly two and a half years. Neither side has accomplished its aims, but both sides have suffered immense casualties. Some of the heaviest casualties occur among the Russian troops.

Tsar Nicholas II sent Russian soldiers to war in 1914, confident of quick victory. The Tsar gave stirring messages to the troops leaving for the front. In the first weeks, the Russians advanced easily. But the war soon proved to be a disaster for Russia. German troops, better equipped and better led, counterattacked and dealt the Russian armies a crushing defeat in the early months of the war. Then it became a bitter war of attrition. There are never enough weapons or ammunition for the Russian troops fighting the Germans and their allies. Supplies are always short and the Russian soldiers often go hungry and have no suitable clothing for the freezing cold of the winters. There is famine in Russian cities. Russian soldiers and civilians die by the millions in a fruitless struggle that seems to have no end.

In March 1917, workers and soldiers in St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd) revolt against the Tsar who had led them into this catastrophic war. The Tsarist government has no support. It is rotten at its core. The Tsar abdicates and flees the city. His government collapses and a new government takes over. Alexander Kerensky is elected prime minister.

Kerensky and his associates believe they must quickly end the war. They order a new offensive against the Germans in the summer of 1917. It is a total disaster. There are enormous casualties. The soldiers who survive turn their backs on the war. They desert in a flood, leaving the front lines to go to their homes. The Russian army collapses.

Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolsheviks, a radical wing of the Communist party, has been in exile in Switzerland. Now the Germans allow him to cross Germany in a sealed train that steams into the Finland Station in Petrograd, in April 1917. Lenin takes charge of the Bolsheviks in Russia and his group soon controls the Communist Party. In November, Lenin leads the Communists in a second revolution in Russia. They oust Kerensky and take over the government. It will be 74 years before the Communists give up power in Russia, and then only after a long Cold War with the United States and its allies.

Russia withdraws from the war, signing an armistice in December 1917. This allows Germany to shift troops from the Russian front to the Western front in France and Belgium. The German generals plan to launch a major offensive to bring the war with Britain and France and their allies to a conclusive end.

But there is no decisive conclusion in 1917. At the small Belgian town of Passchendaele, there is a long and ferocious battle between British and German troops. There are more than 250,000 casualties on each side of the front. But when the battle finally sputters to a halt, almost nothing has changed. The front lines have moved a little here, a little there, but the basic situation is the same, except that over half a million men have been killed or wounded in a few months time in a small patch of cratered mud and waterlogged trenches. Similar indecisive, brutal battles have occurred at many other places along the Western front. Both sides are looking for a way to break the bloody stalemate and achieve victory.

The Germans plan to prevent supplies from crossing the Atlantic to England and France from the United States. German U-boat submarines have been torpedoing British and French ships. Now the Germans announce in January 1917 that they will attack all ships crossing the Atlantic, including those of the United States.

Until this time the United States has maintained its neutrality in the war. There is strong sentiment in the country to remain aloof from the war which, to many, seems to have no sensible cause, no reasonable end, and no great importance to America. In 1916, President Wilson tried to get the warring nations to sit down and negotiate "peace without victory." But each side still thought it could win.

The Germans quickly put an end to American neutrality by sinking several American ships within a short time after their announcement. American public opinion turns. President Wilson can no longer maintain U.S. neutrality.

And so the United States enters the war against Germany in April 19l7. It is fall before American troops are trained, shipped to France, and get into the fighting. But they bring reinforcements to the Allies facing a German army made stronger by troops moved from the Russian front. The German generals hope to take advantage of the additional troops from the Russian front before American troops can be deployed in large numbers. They mount a major offensive. But like so many offensives mounted by each side, there are enormous casualties with little to show for them in the way of land captured. Tens of thousands die in the churned up mud of the battlefields and the front lines barely change. It soon becomes clear that the German push to end the war is a failure.

With the help of American warships, the blockade that has cut off food and supplies to Germany is made even tighter. Hunger and hardship grow within Germany. By the end of 1917 many people in Germany realize that the war cannot be won. The nation wants a scapegoat to blame for the terrible disaster. For some Germans it is the Jews. Anti-Semitism has been present in Germany since medieval times, but before the war many Jews believed that prejudice and discrimination against them was lessening. Now, anti-Semitism returns to Germany in a more virulent form.

In 1917 there are still other important events. Lord Balfour, foreign secretary of Great Britain issues the so-called Balfour Declaration. It is a letter whose purpose is to gain support for the Allied war effort from Jews in Palestine and around the world. The declaration promises "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people..." Then it adds, "...nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine..." Chaim Weizmann, actively trying to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine, has worked hard to obtain the Balfour Declaration. It is only in December 1917 that British troops, under General Edmund Allenby, capture Jerusalem from the Turkish army. Turkey joined the war on the side of the Central Powers, hoping to restore the crumbling Ottoman empire in the middle east.

In 1922, the League of Nations will embody the Balfour Declaration in its plan for the government of Palestine under the British. The promises made in this Declaration underlie the eventual establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 and they will also lead to the Israeli-Palestinian confrontations that still go on.

At the end of 1917, the Italians, fighting against the Germans and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, are defeated in a long battle on Italian soil. Hundreds of thousands of Italian men are killed and hundreds of thousands more are wounded or captured. Slaughter and destruction continue in many other parts of Europe as well.

While Germany itself is not physically damaged, the war produces great hardships. The news from the front lines tells of more and more deaths. In Berlin and elsewhere in Germany, groups are beginning to gather to protest against the war.

Wolf's first year of life is marked by events that will have enormous consequences. But he is just a baby in Berlin, far from the front lines. The Hamburger family tries to live as normal a life as they can. Wolf takes his first steps and learns to grasp a pencil. The events of 1917, the year of his birth, will impact him and affect his life in ways that no one can imagine.

1918.

Reinforced on the Western front by troops from the east, the Germans launch an all-out offensive against the Allies -- Britain, France, and now the United States. There are huge battles engaging millions of soldiers. The German offensive fails to move the Allies back. The only result is more deaths, almost beyond counting.

Most German leaders now see that the war cannot be won. Kaiser Wilhelm reluctantly appoints an emissary to pursue peace negotiations. But the fighting continues and thousands more die each week. The first crack occurs when German sailors mutiny. Then there is a great strike in Berlin, organized by the socialists. Workers and soldiers in Berlin and elsewhere form councils. German Communists, inspired by events in Russia, provide help to these councils. There is an uprising in Bavaria in southern Germany. The Kaiser gives up the throne and secretly leaves the country. The Social Democrats, the largest organized party in Germany, proclaim a republic.

In November 1918, the war comes to an end. Germany is defeated. In a railroad car on a siding not far from Paris, the Germans are forced to sign an armistice that many Germans bitterly resent. Allied armies occupy portions of western Germany. Most of the men in the defeated German army are discharged to return to whatever jobs they can find and to try to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives.

One otherwise undistinguished army corporal from Austria is not discharged. He is twenty-nine year old Adolf Hitler. Hitler leaves the army hospital where he has been recovering from a poison gas attack and returns to Munich where he had enlisted. There, still in the army, he becomes an "education officer" detailed to help immunize the remaining German troops against pacifist and democratic ideas. Some German army leaders believe that they would have won the war had not socialists, communists, and other revolutionaries -- many of whom are Jews -- fomented uprisings on the home front.

Wolf's uncles, Alfred and Erich Levin, return from the battlefield. Alfred has been wounded several times and received the Iron Cross for his bravery. Erich took a bullet in the hip and walks with a limp. Even though the war has been lost, the two men are proud of what they have done for their German homeland.

When the War finally ends Wolf is almost three years old. He has begun to draw. His doting family encourages him, provides him with paper and pencils, and proudly shows the neighbors his drawings. Even as young as he is, it is clear that he has enormous talent. The family and the neighbors can easily recognize the objects that little Wolf draws on the paper. He has the eye of an artist and he already has the ability to reproduce what he can see.

The casualties from the four years of war will never be fully known. In the armed forces of the various countries, there were over 37 million casualties, almost 10 million men killed. Germany lost 2 million men killed, and had another 5.4 million wounded or missing. Russia suffered over 9 million casualties in its armed forces, France over 6 million, Great Britain over 3 million. Tens of millions of civilians died from disease and hunger caused by the war. Half of all the Frenchmen between the ages of 20 and 32 when the war began are dead. Half of all German adult males are dead, wounded, or missing. It is even worse in Russia. It is hard to imagine towns and cities with one-third to one-half of the men gone forever. But that is what happened all over Europe.

These numbers cannot be grasped. They are too large and too horrible. But the impact of such slaughter affects every country. Enormous social, economic, and political changes are set in motion that still affect us today. The victorious Allies are determined that there should never again be such a war. Many Germans agree with this, but some still see war as a way to national wealth and glory. The terrible, senseless war they have just gone through is the primary force affecting the citizens of every country involved. The war makes a compelling impression even on those who were not directly involved. Different people respond to the war in different ways, but no one in Europe can escape its awful impact.

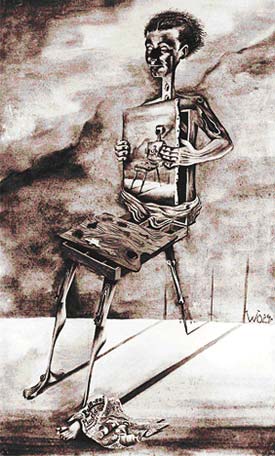

Here are two illustrations created by Wolf:

Wolf self-portrait Paris 1936 |

Master Painter Adolf vs. Master Painter Wolf Wolf Cartoon, Paris 1936 |

WOLF TRAPPED: The Life and Death of a Young Artist in Hitler's Europe

By Robert Follett

As told by Peter Natan

Illsutrations by Wolf

192 pages. 6 7/8 x 8 1/4 inches. Hardbound with jacket.

Over 200 illustrations

ISBN 0-931712-29-7

Publisher's List Price: $29.95

Copies of Wolf Trapped can be obtained from your local bookstore or from a bookselling website. To order directly from the publisher, send a check for $29.95 (for a single copy) to Alpine Guild, Inc. at PO Box 4848, Dillon, Colorado 80435. Publisher will pay shipping and handling costs and sales tax (where applicable). Shipping will be via USPS Book Post, unless other arrangements are made with Alpine Guild.

For more

information about WOLF TRAPPED, visit www.wolftrapped.com, contact us via email

or write or call.